HR&A Advisors, Inc. (HR&A), a leading national consulting firm providing services in real estate, economic development, and public policy, announced that current firm Partner Andrea Batista Schlesinger has been named Managing Partner of HR&A’s Los Angeles office. Paul J. Silvern, who has served as Partner in Charge of HR&A’s Los Angeles office since 2007, will remain an active Partner at the firm and support Andrea in her new leadership position.

The announcement follows the hiring of Lamont Cobb as Director, a fifth generation Californian and third generation Angeleno who brings nearly 10 years of experience in neighborhood planning and economic development efforts for Black and Brown communities, including two years of experience working for the office of Los Angeles City Council District 8.

These staff announcements are part of HR&A’s strategic expansion across the West Coast, including Los Angeles and San Francisco, the Pacific Northwest, and the Southwest to drive equitable development in urban communities. For over 40 years, HR&A has been providing advisory services to the West Coast from its Los Angeles office. Led in recent years by Partners Paul Silvern, Amitabh Barthakur, and Judith Taylor, Senior Advisor Martha Welborne, Managing Principal Connie Chung, and Principal Thomas Jansen, the firm’s game changing projects include developing a citywide economic development strategy for Los Angeles, designing an inclusive participatory budgeting process in Portland, and supporting negotiations for community benefits, anti-displacement, and workforce development efforts around San José’s Diridon Station.

“Since joining the HR&A team nearly four years ago, I’ve had the opportunity to disrupt traditional approaches to economic development, centering on equity as a primary goal and equipping community members with the tools to advance a new vision for their cities,” said Andrea Batista Schlesinger, Managing Partner of HR&A’s Los Angeles office. “As a firm, HR&A is a bridge between generating ideas to realize equity and justice and the implementation of those ideas that change people’s lives. I look forward to leading HR&A’s Los Angeles office, making a demonstrable difference on the matters of consequence in the city and region, while cultivating a team who will go on to be the visionary leaders of America’s cities into the future.”

“We have a mission to improve economic opportunity and quality of life for people who live in cities,” said Eric Rothman, CEO of HR&A. “Since joining the firm in 2017, Andrea’s work has been transformative for our clients with its focus on racial equity and economic justice on projects including criminal justice reform, access to affordable housing, public banking, and more. Andrea’s leadership of our Los Angeles office will strengthen our capacity to promote a just and resilient recovery for cities across the West Coast.”

Andrea Batista Schlesinger and her Inclusive Cities practice works to realize equity and justice. Her work focuses on three core areas:

Equitable Economic Development, including work to develop an initiative addressing the food access crisis in South Los Angeles for the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy and work to advise the Economic Justice Circle, a group of grassroots activists in Pittsburgh, on how to advance an equitable economic development agenda starting with demands for a transparent City budget;

Systemic Change, including work with Trinity Church Wall Street in New York City to address challenges presented by inadequate access to safe housing for those involved with the criminal legal system and who are being released from Rikers Island due to COVID-19; and

Visionary Leadership, including work to support the historic transition plan for Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo, first woman and first Latina to hold this position in the largest county in Texas.

Prior to advising clients on policies, programs, and advocacy strategies at HR&A, Andrea served as Deputy Director of the United States Program of the Open Society Foundations (OSF). In this role, she managed program operations and grant-making portfolios including investments to advance equitable economic development in Southern cities. Previously, Andrea served as a Special Advisor to New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, where she coordinated the Young Men’s Initiative, a $130 million comprehensive package of policy reform and programmatic initiatives designed to reduce the disparities challenging young African American and Latino males.

When we launched this newsletter last April, we said, “times of crisis are times to come together.” We added, “we’re excited to see a growing desire to go beyond a ‘return to normal,’ to proactively shape a stronger, more equitable, more resilient urban life.” The need for bold, fundamental change has only become more acute over the last nine months, as has our desire to work with you to see it happen. Now, that work has new fervor and new champions in the White House.

This week, we are reflecting on this moment with hope. Much work lies ahead. As always, we’re interested in what you are interested in: what are you hopeful for as the Biden-Harris takes shape? Join us in building A Just & Resilient Recovery.

– The Editorial Team

Written by Danny Fuchs, David Gilford, and Ariel Benjamin

Express your views by taking our survey on Local Priorities for a National Broadband Stimulus

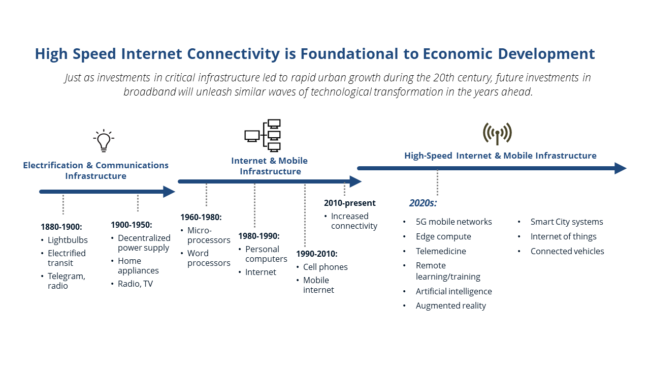

Equitable broadband service is foundational to equitable economic development in the 2020s. Today, 18.4 million American households are unable to access the full range of educational opportunities, jobs, and healthcare, because they do not have affordable, reliable, high-speed internet access. Universal broadband is not only an imperative for a just and resilient recovery from the COVID-19 recession, but it also represents one of the most potentially transformative economic development investments of the 2020s. In New York City’s Internet Master Plan, released last January, for example, we estimated that universal broadband adoption would unlock $142 billion in incremental Gross City Product, create up to 165,000 new jobs, and yield as much as $49 billion in new personal income – estimates confined to the City of New York, in which over 900,000 households do not have a broadband subscription at home.

The Biden-Harris “Build Back Better” agenda calls for closing the digital divide. The questions now are: how much funding will this initiative secure from Congress, and how will it be distributed?

We recently launched a survey on Local Priorities for a National Broadband Stimulus to inform the debate in Washington and Statehouses. Developed as a part of our new Broadband Equity Partnership, a collaboration with CTC Technology & Energy, this survey asks State and local leaders to share their thoughts on Federal funding and policy priorities, Federal broadband fund deployment, and today’s biggest barriers to closing the digital divide. More than five dozen communities have already responded, with more than half of the responses coming directly from government agency leaders or elected officials. We encourage all readers of A Just & Resilient Recovery to share this survey with their elected officials, department heads, and nonprofit community development leaders in their networks before we close the survey on January 15. We plan to publish the results with the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society by the end of the month.

The results of last month’s $900 billion COVID-19 relief package negotiations are informative context for the debate that is forthcoming. Going into December, the bipartisan “compromise” bill included $10 billion for broadband, with $6.25 billion expected as grants to State governments – an approach that would have empowered Governors to close the digital divide in ways befitting the geography, demographics, and market dynamics of their states. The final bill took a different approach: of $7 billion in total funding, more than $5 billion is likely to flow to large Internet Service Providers through funding short-term subsidies and equipment replacement. While the bill does dedicate funds for broadband connectivity in communities around Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), as well as in rural areas and tribal lands, and earmarks funds for broadband mapping efforts, far more locally-tailored investment is needed. Without a more comprehensive approach, subsidies will do little to change the dynamics of the broadband marketplace to foster competition, support greater governmental regulatory authority, or deliver sustainable service affordability.

The leading model for a comprehensive Congressional solution comes from Representative James Clyburn, whose proposed $100 billion Accessible, Affordable Internet for All Act may attract bipartisan support, if former Florida Governor Jeb Bush‘s support for this level of investment is any indication.

Even with an ambitious, well-funded bill, however, we may still be poised for a top-down approach rather than one shaped by states, cities, and counties. Unlike Federal investments in more “traditional” infrastructure, localities have much less administrative capacity to spend on funding for broadband ubiquity. In contrast to transportation departments or housing agencies, information technology agencies do not typically have decades of experience administering urban broadband infrastructure or programmatic investments. The successes of some public service commissions, related public agencies, and utilities in administering the expenditure of Systems Benefit Charge funds may offer lessons, but these efforts have been mainly programmatic, not capital-intensive investment in infrastructure.

Our starting point is the question of how new federal funds will be distributed; we believe that the answer will be informed by actions that states, cities, and counties take. As spending proposals are released, debated, approved, and then designed as Federally administered programs, the next few months will be a critical period for local governments. In New York, the State’s Reimagine New York Commission is likely to shape an answer, while New York City is positioned to leverage Federal funding with $157 million in local capital allocations for broadband. Cities that have initiated partnerships with innovative local providers for free or low-cost services, such as the collaboration among the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles, Starry Internet, and Microsoft will draw from lessons learned and baseline funding needs to position digital connectivity programs to scale.

These are places that have at least nascent and growing capacity to deliver on the local level. They represent a fundamentally different approach to previous top-down investment, policy, and regulatory initiatives from Washington. The Internet represents the most transformative infrastructure for innovation perhaps ever developed. We hope that new Federal funding approaches share that spirit of innovation and grant local governments the resources they need to innovate and build the administrative capacity necessary to ensure that this essential utility is developed more equitably.

We look forward to sharing the results of our survey in the earliest days of the Biden-Harris administration.

For more on HR&A’s work closing the digital divide, see BroadbandEquity.org, and get in touch with Danny Fuchs, David Gilford, or Ariel Benjamin.

Congressional leaders have reportedly been getting closer to an economic stimulus deal, which is expected to provide at least:

- $300 billion in small business support, including repurposed CARES Act funds, to continue supporting programs such as the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and the Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL);

- over $200 billion to extend the Federal supplemental unemployment insurance benefits, to support $300 per week in bonus federal unemployment payments for roughly four months and all pandemic unemployment insurance programs, including the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) and the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC); and

- direct stimulus checks to individuals and families in the range of $600 per person.

As of this writing, the full contents of the proposal are still under discussion. The Democratic demand to retain flexible state and local government aid and the Republican demand for sweeping liability protections for businesses, hospitals, schools and other institutions open during the pandemic appear likely to be jettisoned, in exchange for the extension of unemployment benefits and direct stimulus checks.

The effect of this emerging compromise, while definitely not good news for beleaguered state and local governments, is not all bad news either: in addition to the above amounts, the current draft contemplates direct aid to state and local governmental entities. While total funding for those organizations is down from the $305 billion proposed in the original bipartisan compromise bill to $145 billion, and much state and local flexibility with respect to how to spend funds has been removed, significant state and local government support remains, earmarked for:

- $82 billion for education, including $54 billion for elementary and secondary schools (K-12) through State educational agencies (SEAs) for the purpose of providing local educational agencies with emergency relief funds; $20 billion for higher education institutions, including amounts set aside for minority serving institutions; and $7.5 billion in flexible emergency block grants, empowering governors to decide how best to meet the current needs of students and schools, including private and charter schools;

- $28 billion for transportation, including $15 billion to support public transit systems, $8 billion to support bus systems, ferries and school buses, $4 billion to airports, and $1 billion to Amtrak, all of which will are targeted to preventing furloughs and keeping systems running;

- $25 billion for rental housing assistance to state and local governments through the Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) that must be used for rent, rental arrears, utilities, and home energy costs; and

- $10 billion for broadband, including $6.25 billion for State Broadband Deployment and Broadband Connectivity Grants to bridge the digital divide and ensure affordable access to broadband service, and $3 billion to provide E-Rate support to educational and distance learning providers.

Are these amounts a lot or a little? For context:

- The $25 billion for rental housing assistance through the CRF could help approximately 5 million households for 6 to 9 months, assuming well-designed programs.

- The $3 billion for E-Rate broadband support to educational and distance learning providers could help close the learning gap for over 4.4 million households with students that lack consistent access to a computer by providing them with a hotspot, tablet and support for roughly 7 months.

To learn more about HR&A’s tracking of federal funding for A Just & Resilient Recovery, drop us a line at stimulus@hraadvisors.com.

Written by Danny Fuchs and Kate Wittels

In recent years, leading office developers have leveraged a range of new business models and tech tools to meet demand for more dynamic and amenitized workplaces. In the incipient Work from Anywhere economy, cutting-edge property management will be more critical than ever to sustaining an office product that can compete with makeshift workplaces in homes, hotels, and so-called “third spaces.” The coffee machines and free lunches of yore will no longer cut it.

Moving forward, one of the key questions facing landlords will be whether to develop these services in-house or partner with specialized, third-party providers. In our view, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this question. Variables such as portfolio size, business philosophy, and market niche will inform whether building owners decide to outsource or go it alone. That said, better understanding the universe of possibilities for property management in the remote work era will be crucial to making an informed decision.

On one end of the spectrum, several of the country’s marquee office developers have opted for building in-house services that replicate – and, in some cases, refine – the offerings that might otherwise be delivered by third parties. In 2018, Tishman Speyer, one of the world’s largest office landlords, launched its own coworking venture to compete with offerings by WeWork, Knotel, Industrious, and other coworking providers. Dubbed Studio, Tishman’s coworking product has since been rolled out at its office properties from Boston to LA and Frankfurt and London. Studio’s expansion has proceeded apace during the pandemic, in light of heightened demand for flexible lease terms and well-publicized business woes for WeWork and Knotel among others.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, other owners have opted to partner with a wide range of specialized providers to enhance the tenant experience – and, in some cases, to benefit from the third-party operator’s brand and customer base. The Ion, the first phase of a 16-acre innovation district being developed by Rice University in midtown Houston, is an excellent example of the partner-driven model, with Rice working with specialized firms for coworking facilities (Common Desk), entrepreneurial support (Capital Factory), and a maker lab (TX/RX). Microsoft’s announcement this week that it will move to the Ion is a testament to the project’s appeal in the face of the remote work paradigm.

Common, the co-living management startup (unrelated to Common Desk), is tapping into the expertise of office developers through a national competition to create a network of remote work hubs, described as “an innovative new live/work product for an emerging workforce.” Common frames the partnership as a win/win for office developers, who get to leverage Common’s strong track record in residential management, and for second- and third-tier cities, which may benefit from capturing a segment of the emerging WFA workforce.

Each of these represents a different approach to acquiring, deploying, and managing amenities to improve office building experiences in an increasingly competitive market. As firms consider whether to undertake these activities in-house or outsource them, it is also increasingly clear that complementing these new services with enhanced tenant experience technologies will further improve office owners’ offerings. Some are choosing to develop tech in-house. New York-based RXR Realty, for instance, has built out a range of tech tools through its internal innovation unit RXR Labs, including pioneering a new building management platform called RxWell during the pandemic; among other things, this software enables building owners to efficiently adhere to safety protocols, including social distancing, workforce rotations, and space capacity management. Others are turning to third party software-as-a-service companies, like the Boston-based startup HqO, which promises to “elevate physical office spaces with digital experiences,” a scope which appears to encompass everything from space programming and events to repairs and security. HqO has raised nearly $50 million to date – a level of investment in add-on technology that is far out of the reach of most office building developers or managers.

What may be most interesting about the tech platforms that enable enhanced tenant experiences, however, is not whether they are designed and built in-house or by third parties, but rather how building managers customize the solutions to differentiate their properties. If hundreds or thousands of office buildings in cities across the country adopt a handful of tenant experience platforms – as the venture capital behind the apps is predicting – this tech will quickly become table stakes, not a value-differentiator. Perhaps that is why HqO is making moves to build a “marketplace” feature for its platform, enabling landlords to identify additional technology and real estate vendors across a range of categories, from food delivery and fitness classes to shuttle tracking and security. It’s a bet designed to empower landlords by helping them find more, higher-quality third party vendors for tenant experience improvements, changing the calculus of going it alone or outsourcing these services.

Ultimately, many office landlords may opt for a combination of all three approaches, balancing in-house services and third-party operators with deployment of new technology solutions. The key will be creating a dynamic tenant experience that leverages the best aspects of the physical workplace and fosters the collaboration, camaraderie, and community-building that virtual work arrangements can never fully replicate – and to develop a distinctive mix of offerings that differentiates office buildings not only from other Work from Anywhere offerings, but also from one another.

Amid the largest economic shock in generations, public officials and private investors need to understand how the economic fallout is playing out locally to make informed decisions about investments, policies, and resources required to best position cities for future recovery and growth. HR&A recently assisted Rochester’s Destination Medical Center (DMC) – a public-private partnership that includes the City of Rochester, the Mayo Clinic, and the State of Minnesota – as it updated its 20-year economic development plan to integrate post-pandemic economic projections into its investment strategy.

The DMC’s 20-year plan spells out critical planning and investment decisions in Downtown Rochester, including demand for housing, office, hotel, retail, and other uses – this makes understanding the pace and nature of recovery central to decision-making. To guide planning, HR&A first contextualized how the economic shock in downtown Rochester has compared with national trends based on its unique drivers of activity, including medical tourism and R&D, and then projected economic recovery scenarios informed by precedent pandemics and how public health measures are likely to impact those activity drivers. These projections are being used to inform economic policies and investments in the years ahead.

See HR&A’s detailed analysis of recovery scenarios here

See HR&A’s Analysis and the full DMC plan here

As climate events increase in intensity and frequency, where communities can live and flourish is shifting. Individuals and communities are and will continue to be forced to move. In response, community resettlement must be considered a viable adaptation strategy and incorporated into planning processes and programs.

HR&A Partner Phillip Kash and Analyst Hannah Glosser teamed up with CSRS to offer ten principles to guide program design as cities face the new realities of extreme weather risks.

Read the full report here.

Sign up for our newsletter here!

How is the Thanksgiving meal like a Just & Resilient Recovery? The last eight months have reminded us how interrelated all aspects of urban life are – public health and economic security, open space and democracy. As we continue to work toward a new normal that is more equitable than the last, our strategies more closely resemble a potluck spread than any single course. Click through the images below for a recap of some of our Just and Resilient Recovery thinking to date. Happy Thanksgiving!

Image by Santo Jacobsson. Santo is an illustrator based in NYC and Minneapolis. His main work is multicultural and explores duality. Find more at santojacobsson.myportfolio.com and his Instagram: @santo.jacobsson.

Looking for a recipe for a real side dish in your meal, check out Nova Jacobson’s Sausage Stuffing, courtesy of Candace Damon, and the Morine family Spoonbread with Leftover Turkey recipe from Madison Morine!

|

|

| A JUST & RESILIENT RECOVERY What the meal is built around |

HOUSING SECURITY Safe and warm |

|

|

| SMALL BUSINESS RECOVERY Shop local |

EQUITABLE INVESTMENT Enough to go around |

|

|

| FUTURE OF WORK Live, work, play |

WORKFORCE OPPORTUNITY Our daily bread |

|

|

| OPEN SPACE Picnic in the park |

RACIAL JUSTICE A celebration of herstory |

|

|

| UNIVERSAL BROADBAND Zooming into digital inclusion |

FOOD SECURITY A healthy side |

|

|

| CIVIC PARTICIPATION Making Thanksgiving our own |

TRANSIT INVESTMENT Pulls everything together |

|

|

| DATA INTELLIGENCE Everyone deserves a slice |

BANKING REFORM Keeping all cups full |

|

|

| PUBLIC HEALTH Protect and respect |

CLIMATE RESILIENCE Water, water everywhere |

|

|

| REGIONAL PARTNERSHIP Connecting urban and non-urban |

COMMUNITY ADVOCACY Bringing home the bacon |

The following policy proposal is based on a workshop conducted in September 2020 with: Mason Ailstock (HR&A), Scott Andes (Carnegie Mellon University), Deborah Crawford (University of Tennessee), Bob Geolas (HR&A), Will Germain (Ventas), Bruce Katz (New Localism), Julie Wagner (Global Institute on Innovation Districts), and Kate Wittels (HR&A Advisors).

Read the Full Report Here

Following a challenging election season, the Biden-Harris transition team is now drawing up plans for their policy agenda. Their task is hardly enviable. As we enter 2021, the United States faces four epochal crises: a public health emergency, an economic downturn, climate change, and a reckoning with systemic racism. Addressing these challenges will require a new approach to investing in our communities that stimulates more diverse economic growth, promotes social equity, and taps into knowledge creation that solves, rather than compounds, our twin health and environmental crises.

Federal investment in innovation districts provides a significant opportunity to address these challenges. The antithesis of monocultural research parks, innovation districts combine academic institutions, corporate R&D, startups, and entrepreneurial support organizations in mixed-use neighborhoods that promote creativity and collaboration, often in service of urgent societal challenges. Decades of research now demonstrates that the innovation economy thrives best in porous, multisectoral settings. By leveraging geographic proximity in its allocation of research funds, the federal government can thus dramatically amplify the impact of its R&D dollars. Similarly, by linking educational and workforce programs in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods to nearby innovation districts, the federal government can create a more sustainable economic engine for communities that are currently disconnected from the knowledge economy. Finally, by embracing its role in supporting regional innovation ecosystems, the federal government can reshape the country’s economic geography on a more equitable basis, creating new opportunities for job growth and investment in the nation’s heartland.

To support the growth of innovation districts, federal policymakers must focus on three interlocking policy domains. First, investments in district development will provide the dense physical environments necessary for innovation economies to thrive. Second, investments in talent development will cultivate the expertise needed to drive cutting-edge research and diversify the talent pipeline of local workers and students. Third, investments in research and development will supercharge local and national competitiveness by channeling federal R&D spending to specific innovation geographies.

Building on recent Senate proposals, including the Endless Frontier Act and the Innovation Centers Acceleration Act, there are a number of important actions that the federal government should take.

District Development

The federal government should support the growth of innovation districts in communities throughout the nation by:

- Creating a federal Innovation Zone (IZ) program that funds programmatic and physical investments in districts with emergent innovation ecosystems that, barring federal support, would be unable to capitalize on these latent knowledge economy assets.

- Seeking competitive proposals from local consortia bridging private industry, higher education, and local government.

- Awarding funds to innovation districts that are distributed throughout the country, with an emphasis on supporting places that have yet to emerge as innovation hubs.

Talent Development

The federal government should support the upskilling and reskilling of the nation’s workforce by:

- Supporting the education and recruitment of diverse research and entrepreneurial talent in high-tech fields relevant to specific IZs.

- Requiring co-location of educational and vocational facilities within IZs to facilitate job placement and access to the innovation ecosystem across the skills spectrum and enhance connections to adjacent low- and moderate-income neighborhoods.

- Funding the training of a diverse and resilient labor force with STEM skills through targeted partnerships with community colleges, four-year colleges, workforce investment boards, and the K-12 system.

Research & Development

The federal government should enhance domestic R&D activity by:

- Targeting R&D funding to universities and businesses within specific IZs and incentivizing partnerships between companies, educational institutions, federal research entities, and state and local governments.

- Encouraging commercialization within university settings by amending grantmaking criteria to incentivize applied research and restructuring Technology Transfer Offices into loss-leading, third-party entities operated independently from university administrations.

- Providing seed funding for the creation of IZ-specific venture capital funds that can increase access to financing for new companies.

With a new presidential administration preparing to take office – and the country facing a cascading set of crises – now is the time for the federal government to invest in the growth of innovation districts, particularly in regions that have yet to benefit from the new economy. With a thoughtful and intentional re-alignment of federal policies supporting innovation and economic development, place-based investments in infrastructure, talent, and R&D can leverage the power of proximity to supercharge American innovation and in so doing lay a foundation for a new and more inclusive era of prosperity.

Sign up for our newsletter here!

As we tally the results of our #UrbanismOnTheBallot roundup, we’re also looking forward to this year’s Talking Transition programs in communities that are ushering in new leadership.

The time between Election Night and the first 100 days of an administration presents an opportunity to restore the strength of democracy at the local level – to foster community-driven policymaking that creates the change residents and businesses want. Talking Transition is a program that helps newly elected leaders engage with the communities they represent during this critical moment to shape a more just and resilient administration.

In Harris County, TX, the third most populous in the country, Talking Transition helped connect the new administration to more than 200 community-based organizations. In New York City, the program helped elevate housing affordability to a top administration priority through civic engagement that reached 50,000+ New Yorkers in less than 2 weeks. In Baltimore, an HR&A program modeled on Talking Transition engaged 5 community organizations and trained over 30 Community Data Fellows who led data collection and analysis efforts to ensure equitable data control.

Do you know a newly elected leader who would benefit from this type of inclusion that translates new ideas into meaningful action? Let us know!

Our team of experts follow up and discuss which local ballot measures passed, which failed, and most importantly, why? It’s the #UrbanismOnTheBallot follow up!

| Affordable Housing | Transit |

| Open Space | Equitable Budgeting |

| Digital Inclusion | Tax Responses to Crisis |

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

More local funding for affordable housing

By HR&A Partner Phillip Kash

All of the affordable housing bonds we were tracking passed by healthy margins, with the exception of San Diego‘s where a majority of voters supported the bond (57%) but 2/3 support is needed for passage. The bonds were all for relatively modest amounts:

- Raleigh $80 Million

- Charlotte $50 Million (another $50 million was approved in 2018)

- Denver $40 Million for homelessness

- Baltimore $12 Million

The smaller bond sizes should be more manageable for cities to deploy quickly – an issue that has plagued larger bonds like LA’s 2016 Bond, which have struggled to turn funding into housing at the scale promised and needed. On the other hand, these smaller bonds may be insufficient to make a difference even if they are deployed. This concern is already being raised in Raleigh just days after the City passed its largest housing bond ever.

Voters delivered mixed messages on housing affordability delivered via regulation.

- California voters rejected Proposition 21, which would have given local governments greater power to enact rent regulations. A similar referendum was rejected in 2018, and a law was passed following the rejected referendum capping rent increases at 5% plus inflation, which is viewed by most housing advocates has having had little practical impact.

- In Portland, ME voters issued a split decision – supporting a local rent regulation requirement but rejecting a limit on short-term rentals (think AirBnB). Portland’s rent regulation is far more renter friendly than California’s, limiting rent increases to inflation plus increases in property taxes. A similar rent regulation referendum was rejected three years ago. The rejection of the short-term rental restriction may produce an interesting interaction with the rent regulation restrictions as landlords weigh shifting from long-term to short-term rental.

- Boulder, CO passed a local fee on rental properties intended to fund legal representation for tenants facing eviction. There is a growing movement to create a right to counsel for tenants in eviction court. It remains to be seen how much traction this trend will gain.

- Nevertheless, support for transit in fast-growing metros has increased across recent election cycles. Previous transit initiatives failed in Austin in 2000 and 2014, and Gwinnett County rejected a 2019 transit measure by over 90,000 votes. The influx of new residents to these cities will continue to expand the demand for transit investments as their infamous traffic jams will continue to plague commuters returning to work. The question becomes “who pays for it?” – local residents, the state/region, or the federal government. Many local transit authorities depend on a dedicated source of local funding; the sales tax increase in the Bay Area and property tax increase in Austin provide long-term, sustainable revenues.

- Both the number and dollar value of transit initiatives on the ballot in 2020 were lower than in 2016. We don’t know why that was the case, although certainly, the pandemic and resulting recession may have been factors that affected a reduced number of referenda for transit and other public spending. We also suspect that the lack of a meaningful federal program for transportation, and uncertainty about federal matching dollars, dampened local enthusiasm. To that end, HR&A is hopeful that the Biden-Harris victory in the Presidential election, which will propel “Amtrak Joe” to the White House, is a sign of brighter days ahead for transit funding nationwide.

- In solidly “red” Collier County, FL, over three-quarters of voters approved a second round of funding for Conservation Collier, a 17-year old conservation and recreation program that’s been lauded for its past success in equitable investment. That’s up from 60% in the initial vote in 2002. By increasing taxes on the median home by about $75 a year, the county will raise $250-300 million. In approving the referendum, voters overruled some County Commissioners who had suggested the program ought to rely on donations for new funding. County Commissioner Penny Taylor rebutted, saying “we value authentic Florida… We came together, Democrats and Republicans, and said, ‘[W]e are willing to put money aside for it.’”

- In Rochester, MN, 61% of voters decided to more than make up for $1.7 million in budget cuts that the City Council had determined to be necessary due to COVID-19 fiscal stresses, even though doing so will require raising property taxes by $33 a year for the median homeowner. This collaborative advocacy effort of the Trust for Public Land (TPL) and Rochester Parks and Recreation won in 50 of 52 precincts and by a larger margin than virtually all the top-of-ballot candidates, including President Elect Biden (54%), Senator Smith (51%), and all winning candidates for Rochester School Board and City Council.

- The priciest initiative we followed was Portland, OR’s agreement by almost 2/3 of voters to increase property taxes for the median homeowner by $151 a year in order expand equitable access to parks. The funding – estimated to total $58.6M annually – will fill a $16 million hole in the system’s operating budget due to a drop in recreation fees during the pandemic, obviate the need for at least some of those fees in the future, expand programming for low-income residents, and make a dent in hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of deferred maintenance. Portland voters delivered mixed messages on other urbanist issues – rejecting new transit but welcoming a new police oversight board.

- 770,000 voters (nearly 90%) in Chicago said “yes” to support an “act to ensure that all the city’s community areas have access to broadband internet.” Alderman George Cardenas (12th Ward) sponsored the measure to gauge whether Chicago should do more to provide internet access as the city prepares to ensure 100,000 Chicagoans have access to the internet over the next four years through $25 million from Chicago Public Schools, $20 million from philanthropy, and $5 million in CARES Act funding.

- In Denver, more than 225,000 voters (84%) approved a measure for the city to join a growing list of 120+ Colorado communities that opt out of a State law that prohibits local governments from providing broadband internet service – a measure that passed by similar margins in Englewood, and Berthoud, CO.

- Meanwhile, in the town of Lucas, TX, 2,677 voters (60%) voted against investing $19.2 million in a fiber network to reach all homes. This defeat illustrates the challenges of capital-intensive approaches to broadband in medium and lower-density neighborhoods, as well as the potential for technological innovations that enable lower-cost networks – the type of approach that the City of New York is advancing with its Internet Master Plan.

- A proposal to tax commercial property differently than residential property – that would have yielded an annual estimated $11.5 billion in desperately needed funding for schools and other services – involved an amendment to the 1978 Proposition 13, considered the “third rail” of California politics. With powerful interests and $139 million of total spending by both sides, opponents’ arguments about adverse impacts on commercial tenants during a pandemic and fears that the measure could eventually lead to further Prop 13 changes impacting residential development carried the day.

- Graduated real estate transfer taxes on higher-priced sales in Culver City and Santa Monica attracted some opposition, but were each supported by more than 80% of their voters. Another such measure in San Francisco with more fierce opposition earned support from 58% of its voters. These measures all clearly targeted the new resources to assist local economic recovery, among other purposes.

TRANSIT

Are we waiting on the Feds?

By HR&A CEO Eric Rothman

Our country’s divisions in the national elections were evident in support for local transit initiatives. Overall, voters approved around 90% of transit referenda across the country, though the losses include a few large-scale efforts. We were excited to see resounding voter approval for transit ballot initiatives in two regions where we have done extensive work. In Austin, voters approved two initiatives for a combined nearly $8 billion: Project Connect, which will bring several light rail lines and a new tunnel to the Capital region, and Mobility Elections, which will support walking, cycling, and complete streets. In the Bay Area, voters passed emergency funding support for CalTrain commuter rail, whose ridership has been decimated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

We were disappointed to see voters reject the Get Moving 2020 initiative in Portland, OR and the expansion of MARTA heavy rail in Gwinnett County, GA, which lost by a razor-thin margin of just over 1,000 votes. While transit referenda tend to fare better in bluer metros, the results do not align directly with top-of-ballot choices. In Gwinnett County, 58% of voters cast ballots for Joe Biden, meaning that a significant number of Biden voters opposed the transit measure. Nearly 58% of Portland-area voters opposed the Get Moving 2020 measure, which would have funded 150 transportation projects, despite the metro’s deep-blue political bent.

OPEN SPACE

People love parks

By HR&A Vice Chairman Candace Damon

All 27 of the parks referenda that we were watching won in landslides. Results in Traverse City and Garfield Township, MI, were simply the most extreme example of a nationwide trend: while record turnout delivered a host of very close decisions, including one race decided by two votes, locals committed to a 20-year 0.3 mill levy with 72% of the vote in order to renew a commitment to a recreational authority and its capital and operating budget.

As many of us wonder how the other half our fellow Americans could have voted to affirm values so unlike our own, this author wonders whether a broadly shared commitment to quality open space could provide an opening for dialogue.

Readers may recall we were particularly interested in three referenda, which will create new sources of operating revenue to make parks more equitable and inclusive.

↑ Back to Top

EQUITABLE BUDGETING

Investing in a fairer future

By HR&A President Jeff Hebert

National conversations about social and racial equity tend to focus on Washington personalities and policies, but many injustices, and the means to address them, depend on local government action. Last Tuesday, multiple municipalities took steps to address inequity. San Francisco voters overwhelmingly approved almost $500 million in bonds for homelessness prevention and mental health services, in addition to investments in parks and streets. A Baltimore measure to raise $160 million for affordable housing, schools, community and economic development, and public infrastructure gained over 85% of voter support.

Two other successful initiatives particularly caught our attention. A majority (57%) of Los Angeles County voters supported dedicating funds for additional community investment and alternatives to incarceration for the explicit purpose of correcting racial injustices. Measure J stipulates that the voter-dedicated funds—10% of the County’s locally generated, unrestricted revenues—may not be spent on prisons, jails, or law enforcement agencies. Rather than a one-off budget concession, this apportionment is to remain in effect indefinitely. As Vox’s Roge Karma suggests, this positive vision for the use of public funds—for housing, mental health programs, jail diversion, employment opportunities, and social services—is the other side of activists’ “defund the police” campaigns. Focusing more political energy on what to fund rather than on what to cut may yield more victories like this one in LA County: Karma cites a Reuters/Ipsos poll in which 76% of respondents supported moving “some money currently going to police budgets into better officer training, local programs for homelessness, mental health assistance, and domestic violence” whereas only 39% supported “dismantling police departments” to fund the same types of programs.

Meanwhile, a majority (52%) of Dallas voters approved $3.5 billion in bonds for the Dallas Independent School District (DISD) to repair and upgrade school facilities and invest in school technologies. While this amount will not cover all of the $6 billion in needs identified through DISD’s master planning process, it will fund the renovation of over 200 campuses and the creation of 10 new campuses and 14 replacement schools. DISD will also invest in 4 new Student and Family Resource Centers aimed at addressing racial inequities in historically underinvested neighborhoods—guided by a Child Action Poverty Lab process that HR&A supported. These investments will also prevent adding to a backlog of deferred maintenance, which currently amounts to hundreds of millions of dollars. DISD projects that, as Dallas thrives and the property tax base grows from new construction and appreciation of existing properties, it will be able issue new debt without raising taxes.

DIGITAL INCLUSION

Everyone wants it, but how?

By HR&A Managing Partner Danny Fuchs

Five ballot measures in three states last week demonstrate the crux of the universal broadband problem: everyone wants to address it, voters are supportive of greater local authority to do it, but the details of implementation present obstacles.

As there are growing calls for $100 billion in federal investment for universal broadband – from both the left and the right – we’re excited to be working with local governments, foundations, and innovative broadband businesses to help translate this intention into action at the local level.

TAX RESPONSES TO CRISIS

Formidable, well-funded statewide opposition

By HR&A Partner Paul J. Silvern

We tracked a variety of initiatives that sought to raise new revenues to meet the fiscal challenges of these troubling times. Statewide measures were a split decision, while local measures were mostly approved. Certainly the merits of each measure as the voters saw them mattered, but so also did the sophistication of opposition campaigns and the scale of financial resources that supported them. Voters may also have understood more clearly how proposed local measures could provide direct benefits to solve immediate economic and other problems.

Among the statewide measures with more significant campaigns and war chests on both sides, California’s proposed property tax amendment was declared defeated by a 48%-52% margin, while a graduated income tax amendment in Illinois was defeated by a much wider 55%-45% margin. On the other hand, Oregon’s tobacco products tax won 67%-34% and Arizona’s higher tax on upper-income brackets passed 52%-48%. Among local measures to increase existing taxes or add new ones, Alameda County, San Francisco, Culver City and Santa Monica won their proposals, but a fire protection measure lost once again in San Diego.

The difference in outcomes between statewide and local measures was particularly evident in California: