Written by Judith Taylor and Garrett Rapsilber

Experts have been arguing for some time that we are in the midst of the fourth industrial revolution, with technology driving change at an unprecedented rate. Among the important changes coming is a shift from a fossil-fueled economy to a green one. As with previous transformations, the beneficiaries of that change are uncertain. The decisions we make in the next few years will determine how quickly we build this economy and who enjoys the benefits of this new system.

Many organizations, including city and state governments, have already planned for the emergent green economy, adopting workforce development and sustainability plans with ambitious green job creation and equity targets. Successful implementation of these plans will require the creation and execution of effective workforce development programs.

Yet the lack of national reporting on green jobs since 2012 has left an information gap on even basic characteristics of the green economy. With the Biden administration’s commitments to a carbon-free future, notably an expected $1.0 trillion earmarked for historic investments in infrastructure, clean energy, and zero emissions transportation as part of the Build Back Better Recovery Plan; the administration’s Justice40 Initiative, which states a goal of delivering 40% of the overall benefits of relevant federal investments to disadvantaged communities and tracks performance toward that goal through the establishment of an Environmental Justice Scorecard; and an impending economic recovery, we are at a unique moment to direct both a green and equitable economic future – if we make informed policy decisions.

We recently completed work for the Los Angeles Clean Tech Incubator (LACI) that estimates the size and composition of the green economy in LA and considers the implications for workforce development in that region. We found that the green economy is already larger than most people think and that policy interventions are required to support the inclusive growth of this economy.

“This document provides the evidence that we need to pursue different policies and it should be the blueprint for policymakers and decisionmakers both in the private and public sectors for future investments.”

– Gregg Irish, Executive Director of the City of Los Angeles Workforce Development Board

Our work began with coding almost 1,000 6-digit NAICS codes for the percentage of jobs that are green by industry. This work built upon the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Green Goods and Services Survey, which was discontinued after 2011 due to federal budget cuts but remains the most comprehensive survey of green jobs across all industry sectors. Given the age of this data, we accounted for greening of the economy over the past decade, including emergence of industries and occupations such as micromobility and electric vehicle technicians. With these adjustments we were able to estimate the number of green jobs today and to project the size of the future green economy by leveraging job growth forecasts.

This ground-up approach allowed us to not only create green jobs estimates, but also characterize the green economy with labor information, such as education and training requirements, and demographic information, including race and gender. We found that white people disproportionately hold green jobs. People of color make up 75% of the County’s working-age population but constitute only 65% of the labor force and hold 65% of green jobs, pointing to systemic racial disenfranchisement within the Los Angeles job market. Digging deeper, this disparity in the green economy is not uniform. People of color hold 59% of clean energy jobs but 71% of zero emissions transportation jobs.

Likewise, men disproportionately hold green jobs. While women are approximately half the working age population and hold half of all jobs in LA County, only 37% of green jobs are held by women, due in part to longstanding gender inequity in technology, manufacturing, and the trades. Many in the industry recognize and are working to better align training models to support women and people of color.

To complement the quantitative data from our study, we worked with an advisory group of 23 regional workforce development leaders and interviewed other regional leaders from education, government, labor, non-profits, and green industries. We learned, among other things, that many workforce development programs do not have the capacity to teach both technical skills, such as electric battery maintenance or energy efficiency modeling, an d soft skills, such as professionalism and networking. Underserved populations see higher job placement success when receiving this additional soft skill support. Turning again to the low percentage of people of color holding clean energy jobs, we learned that while educational requirements are one cause for the disparity, other factors include lack of soft skills training, diverse networking groups, and sufficient outreach to communities of color.

Coupling economic data and insights from local leaders, we were able to offer policy recommendations that recognized the Los Angeles region’s unique economic strengths and workforce development ecosystem. For instance, as the most populous county in the nation, Los Angeles County has seven local workforce development boards, including the Los Angeles County Workforce Development Board and the City of Los Angeles Workforce Development Board, which share responsibilities for regional workforce policy and oversight. It will take similarly tailored work in communities across the country to ensure that we are prepared to realize national goals for a greener and more inclusive economic future.

For more details on our work for LACI, HR&A’s green jobs report can be accessed in full here.

Written by Jeff Hebert, Bret Collazzi, and Cathy Li

Communities across America are seeking transformative change: to reform policing and reinvest in communities of color; to rethink tax structures and economic development systems; to make critical but costly investments in transit, energy, and broadband. All of these efforts face obstacles that can delay progress and deflate supporters: the need to overcome inertia and opposition, navigate budget and regulatory complexities, and demonstrate that a break from the status quo is feasible. In that context, the ongoing efforts to transform New York City’s Rikers Island – home to one of the nation’s most notorious urban jail systems – offer important lessons for how visions that once seemed aspirational can make progress toward reality.

The latest efforts to transform Rikers were launched in 2016 with several aims:

- To close the jails on Rikers, which as of 2016 housed 10,000 individuals, nearly 80% of whom were held before trial and 90% of whom were Black or Latino.

- To create a more humane criminal justice system with many fewer people in jail.

- To reimagine the island to honor survivors and promote justice and economic opportunity.

Since 2016, the City has committed to close Rikers by the end of 2027; cut the jail population nearly in half owing to cash bail reform, the decriminalization of low-level offenses, and other reforms; and approved a plan to rebuild smaller, safer, more accessible detention facilities near the borough criminal courts. Last month, the efforts to close Rikers reached an important milestone when the City Council formally embraced “Renewable Rikers,” a vision promoted by justice and environmental advocates to transform the island with green uses and to support economic and environmental justice. Council action begins to transfer the island out of the control of the Department of Correction and establishes a committee to guide reuse of the island that includes formerly incarcerated New Yorkers and justice and environmental advocates, with clear timelines for the City’s commitment to close the jails.

The efforts to close Rikers are still incomplete, and significant obstacles remain. The pandemic has sickened people housed on Rikers, and mass incarceration and mass homelessness continue, leading advocates to launch a new campaign for just reentry. With City budget deficits and elections for Mayor, City Council, and District Attorney looming, the momentum to close Rikers faces pivotal tests. But five years ago, it seemed inconceivable that the City would close Rikers; today there is a path forward and significant political momentum behind that goal.

That shift is a testament to vision and leadership from many groups and individuals. Leaders include organizers of the #CLOSErikers campaign, the Center for Court Innovation, and lifelong criminal justice reformer Herb Sturz. Here, based on interviews with participants and HR&A’s work supporting efforts to plan the future use of the island, we offer lessons for those contemplating similarly ambitious efforts:

Seize the urgency of the moment. Efforts to close the Rikers jails date back at least to the 1970s, led by incarcerated New Yorkers, their families, and justice advocates. These were unable to gain traction until the early 2010s when public attention was caught by damning investigations by the U.S. Attorney’s Office and the Legal Aid Society of violence on Rikers, the national rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the tragic suicide of 22-year-old Kalief Browder after three years on Rikers without a trial. Recognizing the moment, justice organizers launched the #CLOSErikers campaign, led by Rikers survivors and their families. Around the same time, then-City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito appointed an independent commission headed by former New York Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman to study closure and the reforms needed to achieve the goal.

Master the inside/outside game. The north star for advocates’ efforts was securing public support and a commitment from the Mayor and other officials. The #CLOSErikers campaign kept up outside pressure, holding rallies, spotlighting continued instances of abuse, and building an ever-broader constituency, while the Commission, led by respected former public officials like Lippman and Sturz, worked with stakeholders across government and the justice system and crunched the numbers to understand the realm of the possible. The Commission’s work laid out a detailed plan for closure, and the advocacy campaign helped change the public narrative and ensured that the City was firm in closing Rikers in its entirety by a date certain. These efforts laid the foundation for the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice and other agencies to make progress toward reducing the number of people in jail. Five years later, the Renewable Rikers campaign has employed a similar dynamic: a broad coalition led by justice and environmental organizers built political and community support to ensure that plans for the island’s future serve the needs of the individuals and communities most harmed by Rikers, while in the City Council, Council Member Costa Constantinides wrote legislation and navigated negotiations over use of the island.

Build a broad, multidisciplinary base of support. The Commission’s membership included former law enforcement and corrections officials, justice advocates, formerly incarcerated New Yorkers, business leaders, and philanthropists. This mix of voices aired concerns early and ensured the Commission’s recommendations held weight with all corners of the city and carried an aura of inevitability. An early decision by the Commission to study future uses for Rikers Island attracted interest from environmentalists and urban planners. Similarly, the broad coalition behind Renewable Rikers today demonstrates the synergy between justice and climate goals and represents a politically powerful coalition.

Focus on implementation from the outset. While all campaigns focus on what they want to see, the Rikers efforts gave equal weight to how to make it happen. What policy changes were needed to reduce the number of people in jail, and how could they be achieved? What should a smaller, off-Rikers jail system look like, and how should it operate? How long would the plan take and what would it cost? Dedicating time and resources to answer these questions chipped away at justifications for inaction, provided a roadmap for sustained advocacy, and equipped supporters with answers to skeptical audiences. Critical to this focus was assembling a team of credible, mission-aligned analysts. The Center for Court Innovation, the Vera Institute for Justice, and CUNY’s Institute for State and Local Governments led the Commission’s criminal justice analysis, while HR&A, FXCollaborative, Stantec, and others led the planning team that looked at the future use of Rikers. These planning processes adopted justice goals – for the island reuse plan, we began with: How can reuse support justice? – and then developed a process to advance those goals that could stand up to scrutiny and provide actionable guidance to City officials and advocates.

Keep up pressure to secure results. Campaign leaders have driven stakes in the ground to sustain momentum over election and economic cycles. Advocacy groups led by directly impacted people, such as the Freedom Agenda, continue to hold direct actions to keep elected leaders at every level accountable. The Commission, rather than disbanding, continues to support justice reforms required to achieve closure. Justice and environmental advocates built a coalition around Renewable Rikers.

While the efforts to close Rikers are only approaching halftime, the critical shift from aspiration to execution – sought a thousand times over in communities across the U.S. – offers hope for transformational change.

Written by Erman Eruz

Yesterday President Biden signed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan (ARP). As the third COVID-relief bill since March 2020, the ARP will deliver aid to millions in need, including $1,400 direct stimulus checks, expansion of unemployment insurance through September 6 with $300 per week in federal benefits, and an expanded child tax credit program, projected to cut child poverty in half.

In addition, the ARP will deliver over $500 billion in direct aid and other support to state and local governments, which were largely left out of the COVID-relief bill in December This includes:

- $350 billion in direct aid to State, local, and Tribal governments, and territories, more than doubling the $150 billion provided by the Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The new funds can be used with even greater flexibility, including for replacing revenues lost since January 2020, which was not allowed for CRF funds. Other potential uses include: aid to households, small businesses, nonprofits, and industries; investments in water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure; unemployment support and workforce development; and support to health facilities with the costs of protective equipment, testing and vaccination rollout; among others.

- $10 billion for a new Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund to carry out critical capital projects directly enabling work, education, and health monitoring, including remote options. Each state, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia will get $100 million, and the rest will be distributed based on total population, rural population, and proportion of low-income households. Broadband infrastructure investments are especially suited for the use of the funds. For example, Senator Chuck Schumer already announced that New York State’s share of the Fund will go towards the State’s Broadband Investment Program. The Secretary of the Treasury will establish a grant application process within two months. It is not yet clear who will administer the Fund.

- $3 billion in Economic Development Administration (EDA) Grants, double the $1.5 billion included in the CARES Act, to provide flexible funding that can help local governments, downtown organizations, nonprofit institutions, and others plan for recovery and make investments in small business, infrastructure, and economic development projects. 25% of the funding will assist communities that have suffered economic injury as a result of job losses in the travel, tourism, or outdoor recreation sectors. Although the funds will remain available until September 2022, most funding will likely be earmarked much sooner; as with the EDA funds in the CARES Act, Regional EDA Departments will seek to channel the funds to existing projects in the backlog or set up accelerated competitive grant procedures.

- $30.5 billion in Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Grants to help with operating costs, including payroll and personal protective equipment. The funds will be distributed using existing FTA programs, with $26.1 billion for the Urbanized Area Formula Grants and $1.7 billion for Capital Investment Grants. The funds will remain available until September 2024.

- $21.55 billion for Emergency Rental Assistance to augment funds provided to states, localities, and territories through the Coronavirus Relief Fund, to help families pay rent and utility fees. The new funds will add on to the $25 billion made available in the December 2020 COVID-relief bill. Assuming well-designed programs, the new funds could assist an additional over 4 million households for up to 6 to 9 months.

- $5 billion in emergency assistance to secure housing for the homeless, providing flexibility for both congregate and non-congregate housing options, helping jurisdictions purchase and convert hotels and motels into permanent housing, and helping communities provide supportive services.

- $5 billion in Emergency Housing Vouchers to transition homeless and at-risk population to stable housing. Funds will remain available until September 2030.

- $50 billion for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Disaster Relief Fund for 100% reimbursement to State, local, Tribal, and territorial governments dealing with ongoing response and recovery activities from the pandemic, including vaccination efforts, deployment of the National Guard, providing personal protective equipment for critical public sector employees, and disinfecting activities in public facilities such as schools and courthouses.

- $10 billion for the State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI) Program, an Obama-era federal financing program that allows State governments to set up programs that can leverage private capital for low-interest loans, financing non-profits, and directly targeting collateral shortfalls, among other uses.

- $7.17 billion for the Emergency Connectivity Fund to reimburse schools and libraries for internet access and connected devices, administered by Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

To learn more about HR&A’s tracking of federal funding for a just and resilient recovery, drop us a line at stimulus@hraadvisors.com.

Written by Candace Damon, Derek Fleming, Danny Fuchs, and Syed Agmal Ali

Food systems and the food economy in the United States are in crisis. Before the pandemic struck, 35 million Americans were food insecure. That number has since swelled to 50 million. While grocery and restaurant delivery workers were deemed essential, promises of hazard pay faded away, and food processing plants have rivaled carceral facilities as the worst hotspots for coronavirus infection in the country. Multiple organizations estimate that about half of all restaurants have or will close permanently. Food workers are paid little, in some cases exempted from standard minimum wages, and frequently lack protection from poor workplace conditions. At the same time, most food businesses are small businesses that have provided a pathway to wealth for immigrant and low-income families. Texas’s deep freeze has demonstrated that urban food systems are as vulnerable to climate change as to pandemic. As appetites grow for local food, development pressures in fast-growing cities are squeezing out spaces for growing food, creating food products, and delivering them to consumers. Meanwhile, agriculture accounts for 10% of the nation’s carbon emissions, and food makes up a fifth of all household and commercial waste.

Addressing this crisis is central to a just and resilient recovery. The City of New York’s newly released, first ever 10-year food plan recognizes this fact. HR&A is proud to have supported development of the plan, building on several years of work at the intersection of food systems, real estate, economic development, and social justice. We worked with the NYC Mayor’s Office of Food Policy to engage food justice advocacy organizations, businesses large and small, philanthropic foundations, healthcare institutions, and growers from across the region. The commitments outlined in the 10-year plan reflect a diversity of stakeholders.

Food can bring people together – not just around dinner tables, but also to take collective action. In cities across the country, people have stepped up to share food in community fridges and distribute it through mutual aid networks. Restaurants are exploring new ways to generate demand and have been sharing notes. The diversity of stakeholders we engaged in New York City can and should be engaged in cities across the country. Here, we highlight opportunities for different types of HR&A clients to center food systems in their work to build a more just and resilient recovery.

Real estate owners, operators, and developers can:

- Cultivate vibrant food retail experiences. The food halls that proliferated in cities in recent years will need to be reinvented post-pandemic to inspire customers to return and office workers to return downtown. The Ferry Building Marketplace in San Francisco, where we have been working with new owners Hudson Pacific Properties, suggests one way of doing so. What was once an inward-facing, premium-product culinary experience is poised to become an indoor/outdoor destination with more culinary options, more diverse vendors, and more variety in footprints to make the building more accessible to more entrepreneurs, complementing one of the world’s most famous farmers’ markets – a win for Bay Area residents, businesses, and visitors, as well as for shareholders.

- Invest in (or at least promote) local hiring. When HR&A Senior Advisor Derek Fleming and chef Marcus Samuelsson opened a new outpost of renowned Harlem restaurant Red Rooster in Miami, they invested in hiring from Overtown – the “Harlem of the South” – and supporting career advancement for their hires. To date, the project has hired more than 80 individuals, most of whom are from historically marginalized communities. All hires take a four-week training program focused on hospitality sector technical skills that are transferable at the highest levels of the industry, as well as urban farming and hydroponics practices.

- Expand food access creatively. As they engage community stakeholders, HR&A developer clients consistently hear a desire for more grocery stores, which operate at very low margins; national credit grocery tenants are therefore often difficult to attract. For some developers, partnering with food cooperatives that generate community wealth may be a viable option. In South Los Angeles, HR&A worked with the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) and the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy (LAANE) to assess the feasibility of addressing the food access crisis in South Los Angeles through grocery retail that would employ union labor to sell food that is fresh, quality, affordable, and for which there is local demand. We established that one promising avenue was to invest in community leaders who are already addressing barriers to food access in their communities and are championing community ownership models. It’s a strategy that developers should consider, and one that public-private partnerships could incentivize or even mandate.

State and local government should:

- Incorporate the food economy into economic development strategies. Behind the viral promotion of Rhode Island as the “calamari comeback state” at last year’s Democratic National Convention was a campaign to grow the cephalopod into a $60 million industry. Food systems and economic development policy are already intertwined in some states, but every big city and state in the union would be wise to recognize that the food economy and food justice are central to equitable economic development.

- Create spaces for food businesses and entrepreneurship. Governments need to rethink the use of their real estate assets as a platform for food access and entrepreneurship. In Jamaica, Queens, community leaders identified a need to help food entrepreneurs graduating from a nearby incubation program find affordable spaces to launch their businesses and to bring a sit-down restaurant to fill a market gap. With $1 million in State funding, the Greater Jamaica Development Corporation retrofitted stalls at a public food market downtown to create low-cost startup space for food businesses and attracted an established restaurateur to open a new location in downtown Jamaica by providing startup capital.

- Support the smallest entrepreneurs. Street vendors have won recent victories in New York and Los Angeles, legalizing the work of low-income, immigrant entrepreneurs. This requires reimagining both enforcement and support, recognizing that these vendors not only create meaningful value for street life and local retail success, but also are an essential part of economic development in low-income communities. HR&A is working with the Street Vendor Project to invest in green technologies that reduce the environmental footprint of the city’s 4,000 food carts and trucks and provide a safer work environment for these immigrant-owned businesses.

- Rethink municipal governance and management of food systems. Local government agencies regulate food, manage the food supply, and purchase more food than anyone else in many cities. To make progress against goals for public health, education, economic development, and resiliency, cities must embrace government-wide efforts such as the Good Food Purchasing Program and reorganize themselves to meet these needs.

While we believe firmly that both the real estate sector and governments can do more to support stronger, more resilient, more just food systems, we also know that so much of the heavy lifting continues to fall on food advocates, nonprofits, and small businesses. There’s never been a more important time for leaders across the real estate and economic development industries to consider how they can support community-identified, -led, and -controlled models for food access and business – concepts central to the fight for food justice. We believe that the right partnerships can be a win for historically marginalized communities, for economic development, for real estate values, and for American society as a whole.

Written by Candace Damon, Danny Fuchs, and Bret Collazzi

“This is a time of testing. We face an attack on democracy and on truth. A raging virus. Growing inequity. The sting of systemic racism. A climate in crisis. … We will be judged, you and I, for how we resolve the cascading crises of our era. Will we rise to the occasion?”

– Biden Inaugural Address (2021)

“Racist, sexist, and classist policies … have left us with stubborn inequalities in wealth, income, health, and education. … We are facing not only the risks posed by climate change, but also rising nationalism and intolerance on a national and global level, which threaten the social fabric of our city.”

– OneNYC 2050 (2019)

“The challenges that Houstonians face are increasing in size, frequency, and complexity—compounded by exponential population growth, an uncertain and changing climate, economic reliance on the energy sector, and inequitable outcomes in health, wealth, and access to services depending on one’s neighborhood.”

– Resilient Houston (2020)

***

In his Inaugural Address President Biden described the “cascading crises of our era;” he could have been reciting from any number of citywide plans of the last decade. Urban leaders across the U.S. have understood for at least that long that long-term policymaking must focus on economic and racial equity and recognized that climate change and structural racism are the chief existential threats to urban life.

To date, city leaders have used the tools at their disposal – land use controls, local regulations, capital spending – to move the needle on these issues. Minneapolis restricted single-family zoning to address a legacy of racist housing policy. Asheville, N.C. and St. Paul, MN are exploring reparations for Black residents. More than 470 U.S. mayors committed to uphold the Paris Agreement. Boston and New York passed major green building mandates to reduce emissions. Austin, Dallas, and San Francisco are finding new ways to pay for transit, other infrastructure, and equity initiatives locally.

Still, cities have been running uphill against national and global trends, stymied by a lack of federal dollars and an opposing federal agenda on issues ranging from housing to the environment to digital access. Now, as Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer told Bloomberg CityLab, cities have a “partner in the White House who thinks like a mayor.” That gives urban leaders at least four years to advance their plans and – by building a case for what federal actions will have the greatest impacts – to influence what the Biden-Harris Administration prioritizes.

Here are five steps cities can take to position their boldest plans for federal support:

1. Demonstrate how your city’s agenda aligns with the Biden-Harris mandate. Review existing plans to connect the dots between your work over the last several years and the goals of the new Administration. Support might be expected for housing plans that challenge restrictive zoning and expand homeownership for historically marginalized groups, climate projects that create green jobs and promote environmental justice, and a crosscutting focus on racial equity and economic empowerment. Taking a fresh look at existing citywide plans, and the progress made toward those plans’ goals, will allow cities to elevate priorities that tie to the new federal agenda while demonstrating that the city has the will, capacity, and expertise to grapple with and execute on bold thinking.

2. Prioritize projects, programs, and places that are poised for local and national impact. Federal support can be expected for local projects that are bold and visible, but just as important are those that are feasible, likely to accomplish their goals, and ready-to-go. To the extent possible, priority projects should address multiple crises – merging climate and equity goals for example, establish a clear path to implementation – with early approvals in place and an established administering entity, and demonstrate alignment between local and state leadership. With the “Build Back Better” recovery package still months from passage, there is a window for cities to lock in necessary support and to update priority projects and programs for broader and more equitable impact. For instance, as state departments of transportation consider reinvestment in the highway system, cities have the opportunity to push for entrance and exit configurations that reconsider the relationship of cities to their regions and, by pushing for depressed roadways or “lids,” to reknit historically Black and low- and moderate-income neighborhoods deliberately split from CBDs by the initial investment in the interstate system, create new developable land to support inclusive economic agendas, and site open space for civic gatherings. We have supported efforts in Portland, Seattle, Houston, and Hartford that could advance these agendas. Doubtless there are many similarly situated cites.

3. Identify your top 3-5 calls to action for the Administration. In 2015, New York City set a goal to lift 800,000 households out of poverty within 15 years; by 2019, the City had nearly achieved that goal, largely thanks to a $15 minimum wage law passed by the State Legislature at the City’s urging. Numerous federal actions – full funding for Section 8 vouchers, immigration reform, a national $15 minimum wage – could significantly advance cities’ equity and climate goals, especially in states where legislatures preempt progressive urban policy. Similarly, changes to federal rules – such as expedited project approvals or expanded local jurisdiction over telecom assets – could enable progress toward city goals at relatively minimal cost to the federal government. At least six of Biden’s cabinet nominees have led a city or a state, bringing with them an appreciation for how federal action (or inaction) can impact local efforts. Picking the battles with the greatest payoff – and building alliances with like-minded cities, advocates, and congressional leaders – could influence which priorities pick up steam in Washington.

4. Articulate a benefits case for each priority. . Cities should be prepared to demonstrate the economic, social, and environmental impacts of priority projects and programs, both to stand out among peer cities’ proposals and to generate buy-in locally as competing priorities emerge. How many jobs will each project create, of what quality, and for whom? How will the project contribute to the Administration’s stated goals? How could priority federal actions free up local dollars for other efforts? What is the federal government’s return on investment for each dollar contributed, and what local and private sector funding will be leveraged? Cities that develop a clear quantitative benefits case and hone a narrative aligned with the Administration’s agenda will have a leg up when applying for aid and a basis for consensus building at home. New York City’s Renewable Rikers plan – which would close the notorious Rikers Island jail complex, transform the island into a green economy hub, and redevelop polluting power plants into community-serving uses – has done this well: taken together, the plan demonstrates the ability to meet 10% of the city’s renewable energy goal and create 1,500 green-collar jobs, among other benefits, while private capital and public savings would fund more than 25% of project costs.

5. Get creative about marketing to generate excitement. As important as it will be to lobby Congressional representatives and Cabinet officials, cities should also play the outside game – leveraging social media, hometown influencers, and mayoral bullhorns to create buzz that makes their priorities stand out. City leaders can take a page from Miami Mayor Francis Suarez, who in his effort to lure Silicon Valley companies to town has traded Tweets with Elon Musk and taken his pitch directly to tech influencers on the chat platform Clubhouse. Or Danbury Mayor Mark Boughton, who embraced a public spat with comedian John Oliver (and renamed a sewage plant in his honor) to get his city on the map nationally. Beyond drawing attention, such public efforts help cities hone their message about why priority investments are essential, generate excitement among residents and other stakeholders, and build a brand that links their city to the aspirations driving the Administration’s agenda: a rebounded economy, racial equity, and a green energy future.

At a time when urban communities across the country need a jolt of energy and optimism, organizing around bold priorities can build momentum for local initiatives that will pay dividends regardless of cities’ ability to get everything they seek from the federal government. As cities frequently learn from major planning efforts – think the competitions for Choice Neighborhoods or Amazon’s HQ2 – just the act of planning can spark creativity, sharpen project visions, and build consensus around bold change that can then be effected with local funds that would have been otherwise unavailable.

HR&A Advisors, Inc. (HR&A), a leading national consulting firm providing services in real estate, economic development, and public policy, announced that current firm Partner Andrea Batista Schlesinger has been named Managing Partner of HR&A’s Los Angeles office. Paul J. Silvern, who has served as Partner in Charge of HR&A’s Los Angeles office since 2007, will remain an active Partner at the firm and support Andrea in her new leadership position.

The announcement follows the hiring of Lamont Cobb as Director, a fifth generation Californian and third generation Angeleno who brings nearly 10 years of experience in neighborhood planning and economic development efforts for Black and Brown communities, including two years of experience working for the office of Los Angeles City Council District 8.

These staff announcements are part of HR&A’s strategic expansion across the West Coast, including Los Angeles and San Francisco, the Pacific Northwest, and the Southwest to drive equitable development in urban communities. For over 40 years, HR&A has been providing advisory services to the West Coast from its Los Angeles office. Led in recent years by Partners Paul Silvern, Amitabh Barthakur, and Judith Taylor, Senior Advisor Martha Welborne, Managing Principal Connie Chung, and Principal Thomas Jansen, the firm’s game changing projects include developing a citywide economic development strategy for Los Angeles, designing an inclusive participatory budgeting process in Portland, and supporting negotiations for community benefits, anti-displacement, and workforce development efforts around San José’s Diridon Station.

“Since joining the HR&A team nearly four years ago, I’ve had the opportunity to disrupt traditional approaches to economic development, centering on equity as a primary goal and equipping community members with the tools to advance a new vision for their cities,” said Andrea Batista Schlesinger, Managing Partner of HR&A’s Los Angeles office. “As a firm, HR&A is a bridge between generating ideas to realize equity and justice and the implementation of those ideas that change people’s lives. I look forward to leading HR&A’s Los Angeles office, making a demonstrable difference on the matters of consequence in the city and region, while cultivating a team who will go on to be the visionary leaders of America’s cities into the future.”

“We have a mission to improve economic opportunity and quality of life for people who live in cities,” said Eric Rothman, CEO of HR&A. “Since joining the firm in 2017, Andrea’s work has been transformative for our clients with its focus on racial equity and economic justice on projects including criminal justice reform, access to affordable housing, public banking, and more. Andrea’s leadership of our Los Angeles office will strengthen our capacity to promote a just and resilient recovery for cities across the West Coast.”

Andrea Batista Schlesinger and her Inclusive Cities practice works to realize equity and justice. Her work focuses on three core areas:

Equitable Economic Development, including work to develop an initiative addressing the food access crisis in South Los Angeles for the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy and work to advise the Economic Justice Circle, a group of grassroots activists in Pittsburgh, on how to advance an equitable economic development agenda starting with demands for a transparent City budget;

Systemic Change, including work with Trinity Church Wall Street in New York City to address challenges presented by inadequate access to safe housing for those involved with the criminal legal system and who are being released from Rikers Island due to COVID-19; and

Visionary Leadership, including work to support the historic transition plan for Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo, first woman and first Latina to hold this position in the largest county in Texas.

Prior to advising clients on policies, programs, and advocacy strategies at HR&A, Andrea served as Deputy Director of the United States Program of the Open Society Foundations (OSF). In this role, she managed program operations and grant-making portfolios including investments to advance equitable economic development in Southern cities. Previously, Andrea served as a Special Advisor to New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, where she coordinated the Young Men’s Initiative, a $130 million comprehensive package of policy reform and programmatic initiatives designed to reduce the disparities challenging young African American and Latino males.

When we launched this newsletter last April, we said, “times of crisis are times to come together.” We added, “we’re excited to see a growing desire to go beyond a ‘return to normal,’ to proactively shape a stronger, more equitable, more resilient urban life.” The need for bold, fundamental change has only become more acute over the last nine months, as has our desire to work with you to see it happen. Now, that work has new fervor and new champions in the White House.

This week, we are reflecting on this moment with hope. Much work lies ahead. As always, we’re interested in what you are interested in: what are you hopeful for as the Biden-Harris takes shape? Join us in building A Just & Resilient Recovery.

– The Editorial Team

Written by Danny Fuchs, David Gilford, and Ariel Benjamin

Express your views by taking our survey on Local Priorities for a National Broadband Stimulus

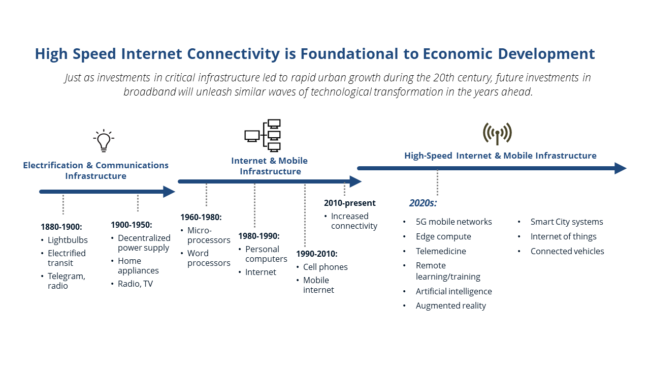

Equitable broadband service is foundational to equitable economic development in the 2020s. Today, 18.4 million American households are unable to access the full range of educational opportunities, jobs, and healthcare, because they do not have affordable, reliable, high-speed internet access. Universal broadband is not only an imperative for a just and resilient recovery from the COVID-19 recession, but it also represents one of the most potentially transformative economic development investments of the 2020s. In New York City’s Internet Master Plan, released last January, for example, we estimated that universal broadband adoption would unlock $142 billion in incremental Gross City Product, create up to 165,000 new jobs, and yield as much as $49 billion in new personal income – estimates confined to the City of New York, in which over 900,000 households do not have a broadband subscription at home.

The Biden-Harris “Build Back Better” agenda calls for closing the digital divide. The questions now are: how much funding will this initiative secure from Congress, and how will it be distributed?

We recently launched a survey on Local Priorities for a National Broadband Stimulus to inform the debate in Washington and Statehouses. Developed as a part of our new Broadband Equity Partnership, a collaboration with CTC Technology & Energy, this survey asks State and local leaders to share their thoughts on Federal funding and policy priorities, Federal broadband fund deployment, and today’s biggest barriers to closing the digital divide. More than five dozen communities have already responded, with more than half of the responses coming directly from government agency leaders or elected officials. We encourage all readers of A Just & Resilient Recovery to share this survey with their elected officials, department heads, and nonprofit community development leaders in their networks before we close the survey on January 15. We plan to publish the results with the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society by the end of the month.

The results of last month’s $900 billion COVID-19 relief package negotiations are informative context for the debate that is forthcoming. Going into December, the bipartisan “compromise” bill included $10 billion for broadband, with $6.25 billion expected as grants to State governments – an approach that would have empowered Governors to close the digital divide in ways befitting the geography, demographics, and market dynamics of their states. The final bill took a different approach: of $7 billion in total funding, more than $5 billion is likely to flow to large Internet Service Providers through funding short-term subsidies and equipment replacement. While the bill does dedicate funds for broadband connectivity in communities around Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), as well as in rural areas and tribal lands, and earmarks funds for broadband mapping efforts, far more locally-tailored investment is needed. Without a more comprehensive approach, subsidies will do little to change the dynamics of the broadband marketplace to foster competition, support greater governmental regulatory authority, or deliver sustainable service affordability.

The leading model for a comprehensive Congressional solution comes from Representative James Clyburn, whose proposed $100 billion Accessible, Affordable Internet for All Act may attract bipartisan support, if former Florida Governor Jeb Bush‘s support for this level of investment is any indication.

Even with an ambitious, well-funded bill, however, we may still be poised for a top-down approach rather than one shaped by states, cities, and counties. Unlike Federal investments in more “traditional” infrastructure, localities have much less administrative capacity to spend on funding for broadband ubiquity. In contrast to transportation departments or housing agencies, information technology agencies do not typically have decades of experience administering urban broadband infrastructure or programmatic investments. The successes of some public service commissions, related public agencies, and utilities in administering the expenditure of Systems Benefit Charge funds may offer lessons, but these efforts have been mainly programmatic, not capital-intensive investment in infrastructure.

Our starting point is the question of how new federal funds will be distributed; we believe that the answer will be informed by actions that states, cities, and counties take. As spending proposals are released, debated, approved, and then designed as Federally administered programs, the next few months will be a critical period for local governments. In New York, the State’s Reimagine New York Commission is likely to shape an answer, while New York City is positioned to leverage Federal funding with $157 million in local capital allocations for broadband. Cities that have initiated partnerships with innovative local providers for free or low-cost services, such as the collaboration among the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles, Starry Internet, and Microsoft will draw from lessons learned and baseline funding needs to position digital connectivity programs to scale.

These are places that have at least nascent and growing capacity to deliver on the local level. They represent a fundamentally different approach to previous top-down investment, policy, and regulatory initiatives from Washington. The Internet represents the most transformative infrastructure for innovation perhaps ever developed. We hope that new Federal funding approaches share that spirit of innovation and grant local governments the resources they need to innovate and build the administrative capacity necessary to ensure that this essential utility is developed more equitably.

We look forward to sharing the results of our survey in the earliest days of the Biden-Harris administration.

For more on HR&A’s work closing the digital divide, see BroadbandEquity.org, and get in touch with Danny Fuchs, David Gilford, or Ariel Benjamin.

Congressional leaders have reportedly been getting closer to an economic stimulus deal, which is expected to provide at least:

- $300 billion in small business support, including repurposed CARES Act funds, to continue supporting programs such as the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and the Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL);

- over $200 billion to extend the Federal supplemental unemployment insurance benefits, to support $300 per week in bonus federal unemployment payments for roughly four months and all pandemic unemployment insurance programs, including the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) and the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC); and

- direct stimulus checks to individuals and families in the range of $600 per person.

As of this writing, the full contents of the proposal are still under discussion. The Democratic demand to retain flexible state and local government aid and the Republican demand for sweeping liability protections for businesses, hospitals, schools and other institutions open during the pandemic appear likely to be jettisoned, in exchange for the extension of unemployment benefits and direct stimulus checks.

The effect of this emerging compromise, while definitely not good news for beleaguered state and local governments, is not all bad news either: in addition to the above amounts, the current draft contemplates direct aid to state and local governmental entities. While total funding for those organizations is down from the $305 billion proposed in the original bipartisan compromise bill to $145 billion, and much state and local flexibility with respect to how to spend funds has been removed, significant state and local government support remains, earmarked for:

- $82 billion for education, including $54 billion for elementary and secondary schools (K-12) through State educational agencies (SEAs) for the purpose of providing local educational agencies with emergency relief funds; $20 billion for higher education institutions, including amounts set aside for minority serving institutions; and $7.5 billion in flexible emergency block grants, empowering governors to decide how best to meet the current needs of students and schools, including private and charter schools;

- $28 billion for transportation, including $15 billion to support public transit systems, $8 billion to support bus systems, ferries and school buses, $4 billion to airports, and $1 billion to Amtrak, all of which will are targeted to preventing furloughs and keeping systems running;

- $25 billion for rental housing assistance to state and local governments through the Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) that must be used for rent, rental arrears, utilities, and home energy costs; and

- $10 billion for broadband, including $6.25 billion for State Broadband Deployment and Broadband Connectivity Grants to bridge the digital divide and ensure affordable access to broadband service, and $3 billion to provide E-Rate support to educational and distance learning providers.

Are these amounts a lot or a little? For context:

- The $25 billion for rental housing assistance through the CRF could help approximately 5 million households for 6 to 9 months, assuming well-designed programs.

- The $3 billion for E-Rate broadband support to educational and distance learning providers could help close the learning gap for over 4.4 million households with students that lack consistent access to a computer by providing them with a hotspot, tablet and support for roughly 7 months.

To learn more about HR&A’s tracking of federal funding for A Just & Resilient Recovery, drop us a line at stimulus@hraadvisors.com.

Written by Danny Fuchs and Kate Wittels

In recent years, leading office developers have leveraged a range of new business models and tech tools to meet demand for more dynamic and amenitized workplaces. In the incipient Work from Anywhere economy, cutting-edge property management will be more critical than ever to sustaining an office product that can compete with makeshift workplaces in homes, hotels, and so-called “third spaces.” The coffee machines and free lunches of yore will no longer cut it.

Moving forward, one of the key questions facing landlords will be whether to develop these services in-house or partner with specialized, third-party providers. In our view, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this question. Variables such as portfolio size, business philosophy, and market niche will inform whether building owners decide to outsource or go it alone. That said, better understanding the universe of possibilities for property management in the remote work era will be crucial to making an informed decision.

On one end of the spectrum, several of the country’s marquee office developers have opted for building in-house services that replicate – and, in some cases, refine – the offerings that might otherwise be delivered by third parties. In 2018, Tishman Speyer, one of the world’s largest office landlords, launched its own coworking venture to compete with offerings by WeWork, Knotel, Industrious, and other coworking providers. Dubbed Studio, Tishman’s coworking product has since been rolled out at its office properties from Boston to LA and Frankfurt and London. Studio’s expansion has proceeded apace during the pandemic, in light of heightened demand for flexible lease terms and well-publicized business woes for WeWork and Knotel among others.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, other owners have opted to partner with a wide range of specialized providers to enhance the tenant experience – and, in some cases, to benefit from the third-party operator’s brand and customer base. The Ion, the first phase of a 16-acre innovation district being developed by Rice University in midtown Houston, is an excellent example of the partner-driven model, with Rice working with specialized firms for coworking facilities (Common Desk), entrepreneurial support (Capital Factory), and a maker lab (TX/RX). Microsoft’s announcement this week that it will move to the Ion is a testament to the project’s appeal in the face of the remote work paradigm.

Common, the co-living management startup (unrelated to Common Desk), is tapping into the expertise of office developers through a national competition to create a network of remote work hubs, described as “an innovative new live/work product for an emerging workforce.” Common frames the partnership as a win/win for office developers, who get to leverage Common’s strong track record in residential management, and for second- and third-tier cities, which may benefit from capturing a segment of the emerging WFA workforce.

Each of these represents a different approach to acquiring, deploying, and managing amenities to improve office building experiences in an increasingly competitive market. As firms consider whether to undertake these activities in-house or outsource them, it is also increasingly clear that complementing these new services with enhanced tenant experience technologies will further improve office owners’ offerings. Some are choosing to develop tech in-house. New York-based RXR Realty, for instance, has built out a range of tech tools through its internal innovation unit RXR Labs, including pioneering a new building management platform called RxWell during the pandemic; among other things, this software enables building owners to efficiently adhere to safety protocols, including social distancing, workforce rotations, and space capacity management. Others are turning to third party software-as-a-service companies, like the Boston-based startup HqO, which promises to “elevate physical office spaces with digital experiences,” a scope which appears to encompass everything from space programming and events to repairs and security. HqO has raised nearly $50 million to date – a level of investment in add-on technology that is far out of the reach of most office building developers or managers.

What may be most interesting about the tech platforms that enable enhanced tenant experiences, however, is not whether they are designed and built in-house or by third parties, but rather how building managers customize the solutions to differentiate their properties. If hundreds or thousands of office buildings in cities across the country adopt a handful of tenant experience platforms – as the venture capital behind the apps is predicting – this tech will quickly become table stakes, not a value-differentiator. Perhaps that is why HqO is making moves to build a “marketplace” feature for its platform, enabling landlords to identify additional technology and real estate vendors across a range of categories, from food delivery and fitness classes to shuttle tracking and security. It’s a bet designed to empower landlords by helping them find more, higher-quality third party vendors for tenant experience improvements, changing the calculus of going it alone or outsourcing these services.

Ultimately, many office landlords may opt for a combination of all three approaches, balancing in-house services and third-party operators with deployment of new technology solutions. The key will be creating a dynamic tenant experience that leverages the best aspects of the physical workplace and fosters the collaboration, camaraderie, and community-building that virtual work arrangements can never fully replicate – and to develop a distinctive mix of offerings that differentiates office buildings not only from other Work from Anywhere offerings, but also from one another.